Abdulrazak Gurnah

|

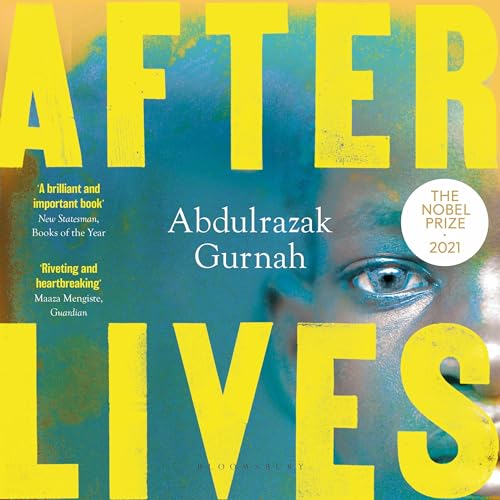

Publisher's summaryBloomsbury presents Afterlives by Abdulrazak Gurnah, read by Damian Lynch.Restless, ambitious Ilyas was stolen from his parents by the Schutzruppe askari, the German colonial troops; after years away, he returns to his village to find his parents gone and his sister, Afiya, given away. Hamza was not stolen but was sold; he has come of age in the army, at the right hand of an officer whose control has ensured his protection but marked him for life. Hamza does not have words for how the war ended for him. Returning to the town of his childhood, all he wants is work, however humble, and security - and the beautiful Afiya. The century is young. The Germans and the British and the French and the Belgians and whoever else have drawn their maps and signed their treaties and divided up Africa. As they seek complete dominion they are forced to extinguish revolt after revolt by the colonised. The conflict in Europe opens another arena in East Africa where a brutal war devastates the landscape. As these interlinked friends and survivors come and go, live and work and fall in love, the shadow of a new war lengthens and darkens, ready to snatch them up and carry them away. ©2020 Abdulrazak Gurnah (P)2020 Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Product Details Unabridged Audiobook Language: English Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Whispersync for Voice-ready Whispersync for Voice-ready Family Life World War I Ihmiskohtalot siirtomaavallan ytimessä.Vuoden 2021 nobelisti Abdulrazak Gurnah on unohdetun Afrikan ääni, historian melskeisiin hävinneiden siirtomaiden kertoja, jolla on taito löytää suurista tragedioista hiljaista kauneutta.1900-luvun alussa Saksan Itä-Afrikassa elämä on levotonta. Sorretut nousevat kapinaan kerran toisensa jälkeen, ja siirtomaajoukot tukahduttavat liikehdinnän verisesti. Historian juurettomiksi jättämät elämät kietoutuvat toisiinsa, koska elettävä on, tapahtuu maailmassa mitä tahansa. Ilyas karkaa lapsena kotoa ja päätyy saksalaisten sotilaiden kasvattamaksi, eikä enää tiedä kenelle olla uskollinen. Ilyaan hylätty sisar Afiya raataa kuin orja kotikylässä. Nuoren Hamzan kohtalo on päätyä saksalaisten sotilaspalvelijaksi ja sitten siirtomaavaltojen sotaan. Hamzan ja Afiyan kohtaaminen sytyttää toivon tulevasta, mutta horisontissa nousevat jo uuden sodan pilvet. "Vain harvoin saa avata kirjan ja havaita, että sen lukeminen muistuttaa rakastumista. Uskaltaa tuskin hengittää ettei lumous rikkoutuisi.” The Times Tansanialle nyt kuuluvassa Sansibarissa vuonna 1948 syntynyt Abdulrazak Gurnah lähti maasta poliittisena pakolaisena 18-vuotiaana ja on sen jälkeen asunut Isossa-Britanniassa. Gurnah kirjoittaa englanniksi ja on julkaissut kymmenen romaania sekä useita novelli- ja esseekokoelmia. Hän on Kentin yliopiston englannin kielen ja postkolonialistisen kirjallisuuden emeritusprofessori. Hän on useilla aiemmilla teoksillaan ollut Booker-ehdokkaana. Nyt suomeksi ilmestyvä Loppuelämät on hänen tuorein romaaninsa vuodelta 2020. Kirjailija: Abdulrazak Gurnah Lukija: Jukka Pitkänen Kääntäjä: Einari Aaltonen Nobel-palkinto 2021 |

Gurnah-AfterlivesSisEng1 Khalifa was twenty-six years old when he met the merchant Amur Biashara. At the time he was working for a small private bank owned by two Gujarati brothers. The Indian-run private banks were the only ones that had dealings with local merchants and accommodated themselves to their ways of doing business. The big banks wanted business run by paperwork and securities and guarantees, which did not always suit local merchants who worked on networks and associations invisible to the naked eye. The brothers employed Khalifa because he was related to them on his father’s side. Perhaps related was too strong a word but his father was from Gujarat too and in some instances that was relation enough. His mother was a countrywoman. Khalifa’s father met her when he was working on the farm of a big Indian landowner, two days’ journey from the town, where he stayed for most of his adult life. |

| 2 Ilyas arrived in the town just before Amur Biashara’s sudden death. He had with him a letter of introduction to the manager of a large German sisal estate. He did not see the manager, who was also part-owner of the estate and could not be expected to make time for such a trifling matter. Ilyas handed in his letter at the administration office and was told to wait. He was offered a glass of water by the office assistant who also made probing conversation with him, assessing him and his business there. After a short while, a young German man came out of the inner office and offered him a job. The office assistant, whose name was Habib, was to help him settle in. Habib directed him to a school teacher called Maalim Abdalla who helped him to rent a room with a family he knew. By the middle of the afternoon on his first day in the town, Ilyas was employed and accommodated. Maalim Abdalla told him, I’ll come by |

| 3 He picked him out with his eyes during the inspection on that first morning. The officer. That was in the boma camp where they were taken to join the other recruits who had been rounded up earlier. from the depot to the boma their escort hectored and mocked and hurried them on, ahead and behind them and sometimes beside them. You’re a bunch of washenzi, they said. Feeble fodder for the wild beasts. Don’t swing your hips like a shoga. We are not taking you to a brothel. Straighten your shoulders, you cocksuckers! The army will show you how to stiffen that backside. |

| 4 They had no word from Ilyas but that was nothing to worry about, Khalifa said. ‘Dar es Salaam is a long way away. We should not expect to hear for a while. We’ll get news when someone comes from Dar es Salaam or perhaps he’ll send us a note. Sooner or later we’ll hear from him.’ In the early days when she went to live with Bimkubwa and Baba Khalifa, Afiya slept on a thin kapok mattress on the floor in the same room as they did. There was a room in the backyard that was used as a store. The basket of charcoal was kept in there, and some old pots and sticks of furniture, which were bound to come in useful one day. Khalifa said he would clean it up and prepare it for her. It would need a coat of limewash to kill off the bugs but should be a comfortable room after that. There was another store room at the front of the house with its own door. ‘We can move the junk in there,’ Khalifa said. ‘There’s no hurry. First let her get used to us here. She is only |

| 5 The officer had the two-room apartment at one end of the upstairs block on the right-hand side of the boma. It had a small bedroom and another room with two comfortable chairs and a small desk where the officer sometimes sat down to write. There were seven rooms upstairs altogether, a replica of the downstairs layout, and there was a hierarchy to the arrangement. The two rooms at one end for the use of the commanding officer stood next to a large room in the middle of the block that was the mess, then came a room for each of the other four officers, beginning with the medical officer and ending with the Feldwebel, who had the small room at the far end because he was the lowest in rank. The other three officers in the boma had their rooms in the smaller building facing the gate, whose downstairs served as the infirmary and the padlocked store. The store contained provisions for the officers’ mess: tins of European delicacies and bottles |

| 6 They talked about the war in Tanga for many weeks up and down the coast, but for most of them it was quiet after the disastrous attack. It was as everyone had anticipated: the British were no match for the schutztruppe. As word travelled down the coast from Tanga, rumour expanded and embellished the ferocity and discipline of the askari and the shambolic panic of the Indian troops, who it was assumed must have led the panic. Khalifa said they were bound to hear from Ilyas about this German victory – he would not be able to resist singing the praise of the schutztruppe – but they heard nothing from him. |

| 7 One night a detachment of five led by the officer and including Hamza headed for a German mission called Kilemba, which they hoped the British command had not yet reached. The British practice practice was to close all German outposts, farms or missions, to prevent the schutztruppe from receiving supplies there. The German civilians were treated with the courtesies befitting citizens of an enlightened combatant nation and were taken away to Rhodesia or British East Africa or Blantyre in Nyasaland where they could be interned by other Europeans until the end of hostilities. |

| 8 Their boat rounded the breakwater in evening twilight and the nahodha ordered the sail lowered as he made a cautious approach into harbour. The tide was out and he was not sure of the channels, he said. It was after the kaskazi monsoon and in the period before the winds and currents turned south-easterly. Heavy currents at that time of year sometimes shifted the channels. His boat was heavily laden and he did not want to get stuck on a sandbank or to hit something on the bottom. In the end, after debating the matter with his crew, he thought it was too dark to approach the quay in safety, so they dropped anchor in shallow water and waited for morning. |

| 9 Hamza slept by the doors of the warehouse that night because he had nowhere else to stay. He wandered the streets for a while looking for places he knew, but he recognised very little and often did not know where he was. He followed the movement of the crowds and after a while found himself unexpectedly on the shore road. He followed that with a small thrill of recognition and walked on to look for the house where he had lived in his youth, but he could not find it. He thought he had found the right area but perhaps the house was knocked down and something |

| 10 That same afternoon, after the miserable lunch in Khalifa’s house, Hamza went to the market to spend the five shillings given to him as an advance. He bought a candle for his room, and a roll of thick straw matting and a cotton sheet. He stretched out on the matting and groaned as the familiar sharp pain ran through him. After a few minutes its intensity eased and he let his body find whatever rest it could. He ran his hand over the ugly scar on his hip and massaged the healed muscle. It will get better. It was better. There was nothing else to be done. This town that he barely recognised was the nearest place to home he had. The pain will get better. |

| 11 It had become so that she thought of him all the time. When he came to the house in the morning for the bread money, she restrained herself from speaking to him in case Bi Asha heard her. In her book of sins speaking to a man was equivalent to making an arrangement for a secret meeting with him. Hamza said, Habari za asubuhi and she said, Nzuri, and handed over the basket and the money instead of touching him or pressing herself against him. When she passed his room and could see the window was open, she had to resist the temptation to lean in and talk for a moment |

| 12 ‘Good fortune is never permanent, if it comes at all,’ Khalifa said on the third night of Idd as they sat on the porch. ‘It’s only months that you’ve been with us but it seems that I have known you for longer. I have become used to you. I knew from the start that there was something alive behind your zombie appearance. You looked as if you were about to collapse in a heap in front of me when you first arrived. Now look at you. You have found work that suits you and you have even pleased that slow-witted miser of ours, only you need to ask him for a pay rise now that you’ve turned out to be a competent carpenter. Oh, no, you’re going to be the saint who will wait humbly for his desserts to come to him! |

| 13 It was a time of ease for Hamza compared to preceding years. The strain in their living arrangement with Bi Asha and Khalifa lessened as the weeks and months passed by or maybe they became inured to it. They found ways of avoiding each other without seeming to be at loggerheads, of not seeing Bi Asha’s accusing looks and not hearing her growling undertones. Hamza learned to keep out of her way so well that often he only saw her briefly when he came home from work in the afternoon, although her voice was never far away. Afiya was always the first up, but Hamza was usually usually awake, unable to sleep deeply once it was light. She made the tea while he washed and then he left the house before Khalifa and Bi Asha came out of their room. |

| 14 Afiya delivered her child at home, attended by the midwife who had had a hand in the arrival of scores of other babies in the town. Like many others, Afiya preferred to go into labour in the presence of women she knew than to suffer the attentions of complete strangers, so despite the administration’s Maternity Health campaign she did not go to the new clinic for the birth. The midwife was sent for as soon as her waters broke, as was Jamila who had promised to be with her during the birth. Her labour started in late afternoon and went on through the night and into the late morning of the next day. Hamza was sent to the room used to receive guests, where Khalifa also took refuge. |

| 15 One mid-morning in March the following year a policeman on a bicycle rode up to the Biashara Furniture and General Merchandise timber yard. It was raining lightly, hardly spotting his khaki, the end of the vuli rains, the short rains. The policeman was of medium height, with a thin mild-looking face and a small nervous twitch around his left eye. He leaned his bicycle under cover and entered Nassor Biashara’s office. |

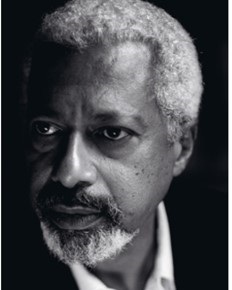

ABDULRAZAK GURNAH (s. 1948) tuli

hänelle myönnettiin Nobelin kirjallisuuspalkinto 2021. Hän

on kirjoittanut kymmenen romaania, joista Paradis

ja Ved havet (tanskaksi vuonna 2022 ja

2023) valittiin Booker-palkinnon ehdokkaaksi.

Hän on emeritusprofessori ja on

opetetaan englanniksi ja postkolonialistiseksi

kirjallisuutta Kentin yliopistossa.

Gurnah syntyi Sansibarissa ja

muutti Isoon-Britanniaan, kun hän

oli 20 vuotta vanha. Hän asuu Canterburyssa

ABDULRAZAK GURNAH (s. 1948) tuli

hänelle myönnettiin Nobelin kirjallisuuspalkinto 2021. Hän

on kirjoittanut kymmenen romaania, joista Paradis

ja Ved havet (tanskaksi vuonna 2022 ja

2023) valittiin Booker-palkinnon ehdokkaaksi.

Hän on emeritusprofessori ja on

opetetaan englanniksi ja postkolonialistiseksi

kirjallisuutta Kentin yliopistossa.

Gurnah syntyi Sansibarissa ja

muutti Isoon-Britanniaan, kun hän

oli 20 vuotta vanha. Hän asuu Canterburyssa

Tekijän valokuva: Mark Pringle Painettu kirja ISBN 978-87-434-0272-5 Ebook 1.0 ISBN 978-87-434-0273-2 E-kirjatuotanto Bonnierförlagen 2022 Tästä kirjasta saa kopioida vain 14. kesäkuuta annetun tekijänoikeuslain sääntöjen mukaisesti 1995 myöhemmillä muutoksilla. Gutkind Forlag • Laederstraede 9,1. • DK-1201 Kööpenhamina K gutkind.dk • n gutkindforlag |

|

PageTop |